Drama in China: The Costumes…

Posted on July 21, 2021 by August-Phoenix-Mercantile

This is Part IV of a series of articles that is part theater history, part personal retrospect, from a time long ago when I was known in medieval society as Lao Tao-sheng – “Old One, Born to Tell Tales.” My own story started with performances of Waley’s “Monkey” at medieval themed feasts, and culminated in a “One Monkey Show” – a solo presentation of the first seven stories from “The Journey to the West” over the course of seven hours, one August day circa 1983-85 (memory fails as to the exact date). A synopsis of my resume is included in Part I of this series. Text in bold indicate research notes that I applied to my performances. My personal comments are in italics where I need to differentiate them from my research.

You will recall from my previous installment that there was as much emphasis on the character roles as the plot of the play. This theme was carried through into the costuming aspects of Chinese dramas.

There were 300 standard items designed to denote a character’s type, age and social status, through a combination of colors, design, ornament and accessories. Materials included silks, satins and brocades, ornamented with motifs that included clouds, fish scale, rippling water, waves, plants, and and animals; costumes for imperial characters were ornamented with phoenixes (feminine) and dragons (masculine). Color was always symbolic. When a costume wore out, it was replaced with a replica in the same style and ornamentation, but never in the same exact shade.

Opera costumes were made for character roles rather than for specific plays. Although they were based on historic models, costumes could be a fusion of historic styles dating between the 7th – 19th centuries. It was not uncommon for robes to be mixed with footwear, hats and accessories from different periods, and costumes did not need to match the time period the play was set in. (It was this reference to anachronism that gave me leave to combine elements from a variety of costumes that I already had, to clothe the Monkey King for my One Monkey Show. Some of those pieces are collected in the photo that introduces this page.)

Between performances, theater costumes were stored in a chest, in a specific order. It became customary to place a patchwork costume called a fu-kuei i (garment of honor and wealth) on top. The patches were multicolored and symbolized uncertainty but with bright hope of the future, and was worn by those playing the roles of poor scholars or distressed women of virtue. It was placed at the top to bring good fortune to the actors who played those roles.

A small sampling of the more recognizable costumes

- Mang Robe – a long loose formal robe with a round neck and the skirt slit up the sides (Ming Dynasty). White cuffs were sewn onto the sleeves, and a stiff belt inlaid with with jades and small mirrors, worn around the hips like a hoop (Song Dynasty). (I made a belt for a non-Monkey costume from a wooden embroidery/quilting hoop, which I wrapped in black satin ribbon and glued mirror squares to it from a shattered disco ball. It was more comfortable to wear than I expected.)

- Women actors could also wear a mang robe, knee length and worn over a pleated skirt (Song Dynasty) or a panel skirt (Qing Dynasty). Both male and female roles could also be robed in p’ei or tieh-ts’ – informal flowing robes made from silk or satin and unadorned.

- Shui hsiu – Water sleeves, shown below (which I believe evolved from T’ang Dynasty court dancers.) They were made of silk and extended 2-3 feet beyond your fingertips. (Mine were attached to my under tunic and only extended about 10″ beyond my fingertips, which was all the sleeve I could manage : )

- Fa i – a sleeveless flowing cape worn by Taoist magicians. Another sleeveless cape, called a tou p’eng, was often red, with a low collar, worn to indicate the actor was traveling, or out of doors at night or in bitter weather.

- Chia sha – a red robe decorated with a brick pattern, worn sling across the left shoulder by Buddhist dignitaries.

- Pei’ hsin – a knee-length sleeveless garment that opened down the front, usually worn over pants or a skirt for women’s roles.

- K’ai-k’ao (or Ta-k’u-qo) – a stylized versions of armor worn by the Heroic Warrior, usually made from stiff satin that was heavily embroidered in fishscale pattern (the costume at right was my attempt at replicating a warrior’s costume, made from heavy moire with silk facings. The undershirt was cotton with white sleeves and a silk skirt. The jacket was embroidered in gold fishscale by Merrilee Humason, known in medieval society as Baroness Anastasia.

...A cap of the Three Mountain's Phoenix flying crowned his head, And a pale yellow robe of goose-down he wore on his frame. His boots of gold threads matched the hoses of coiling dragons, Eight emblems like flower clusters adorned his belt of jade...

The warrior’s robe evolved in more modern eras to include ‘armor panels’ that hung from the waist to the ground both front and back, and a round collar (like a cangue) at the neck that supported four pennants on the actor’s shoulders (which I believe symbolized the armor he led).

Mandarin patches on formal court robes came into being during the Ming Dynasty and would show up in opera costumes after that period. Horseshoe cuffs date to the Qing Dynasty. There are a number of other items like pants, shirts, vests, turbans and sashes that I do not cover here.

The Colors

Some colors were reserved for specific styles of robes for specific roles. This is a general overview and is not delineated by robe style:

- Yellow was reserved for the roles of Emperor, Empress, Prince, and Dowager Mother.

- Red was worn by court officials and army commanders, as well as the wives, daughters and concubines of the Emperor.

- Crimson was worn by barbarian emperors and sometimes by military advisors.

- Generals wore green, pink, orange, white or turquoise depending on their age.

- Black denoted a nobleman with a cruel nature, whose makeup would match.

- Blue indicated a statesman, sometimes a dishonest one.

- White was the color of mourning in China from the Yuan Dynasty.

I have written an article for a separate series on Symbolism in Chinese Embroidery, which is accessible here via a downloadable pdf.

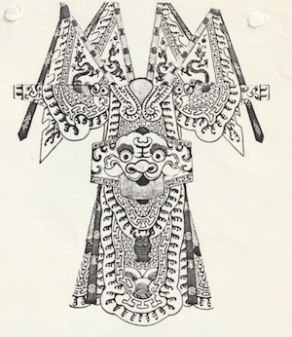

There were 100 types of headwear worn on the Chinese stage. You could tell how important the character was by how ornate their hat or headdress was.

Warriors wore k’ui helmets, made from beaten metal and augmented with pearls and colored balls of velvet suspended on wires. (I believe this is fairly modern, but may have been highly stylized versions of actual military helmets from the T’ang and Song Dynasties.)

Barbarian Warrior helmets included a pair of very long pheasant feathers, and also a pair of long animal tails (foxes possibly) that hung down their backs. (I have seen modern Chinese dramas where these pheasant feather helmet were worn by women warriors; I suspect the one at left might be an example.)

Warriors might also wear a soft beret (Monkey is often depicted with one).

Officials and Scholars wore a variety of hat styles, nearly always in black until more recent times, sometimes in stiffened gauze, with or without side flaps or back ribbons, embroidered or not, depending on their degree. Emperors wore a version of the hat listed above, usually with side or back flaps, and ornamented depending on the formality of the role.

Empress headdresses became quite elaborate, made from beaten gold, ornamented with phoenixes and covered with kingfisher feathers (Song Dynasty).

Noblewomen, especially courtesans or dancers, would ornament their hair with elaborate ornaments in lieu of a hat or headdress (T’ang Dynasty). Common people could wear broad straw hats, or head scarves or turbans, depending on their character. Men could also wear their hair in a topknot, women’s hairstyles were generally braids (for a young girl) or buns (for an adult woman).

The Footwear

Military commanders wore a high soled boot called a sueh-ts was developed exclusively for the stage. Made of silk, they were highly embroidered to match their robes. Soldiers and servants wore ankle boots with soft soles called k’uai-sie. The soft, short boots were necessary for the acrobatics that actors depicted as battle scenes.

Women wore soft satin slippers with flat soles, which could be ornamented with silk tassels and embroidery depending upon the social standing of the character. Common people and especially laborers could wear straw sandals.

The Dynasties

The dynasties listed in this text point to the earliest time period that these articles would have been worn. Here is your secret decoder ring:

- T’ang Dynasty – 608-907 (7th-10th centuries)

- Song Dynasty – 960-1279 (10th-13th centuries)

- Liao Dynasty – 916-1125 (not referenced in this article but provided here to fill in the gap)

- Yuan Dynasty – 1271-1368 (13th-14th centuries, overlapping with the Song Dynasty)

- Ming Dynasty – 1368-1644 (14th-17th centuries)

- Qing Dynasty – 1644-1911 (the end of dynastic rule in China)

Materials I have referenced in this segment include:

- 5,000 Years of Chinese Costumes by Zhou Xun and Gao Chunming, edited by The Chinese Costumes Research Group of the Shanghai School of Traditional Operas, published by China Books & Periodicals, Inc., San Francisco, California 1987 (the English version).

- The Classical Theatre of China by A.C. Scott, Greenwood Press Publishers, Westport, Connecticut, 1957

- Chinese Theater by Kalvodova Si s-Vanis, Spring Books, London, 1957

- Color photos in this section courtesy of Cheri Dohm, known in medieval society as Sunjan Temujin.

“What I would learn next, will be explained in the next chapter”

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- More

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

Category: The StorytellerTags: Chinese theater, MonkeyKing

2 Comments on “Drama in China: The Costumes…”

Thanks for your note! As an anti-spam measure, comments are moderated and will appear once they are approved :)Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed.

So did Monkey wearing yellow mean he had delusions of imperial grandeur?

Yes, he was after all, King of Fruit Flower Mountain, which was his universe until he ventured out to the surrounding kingdoms.